Charged With Possibility: Umicore (UMI)

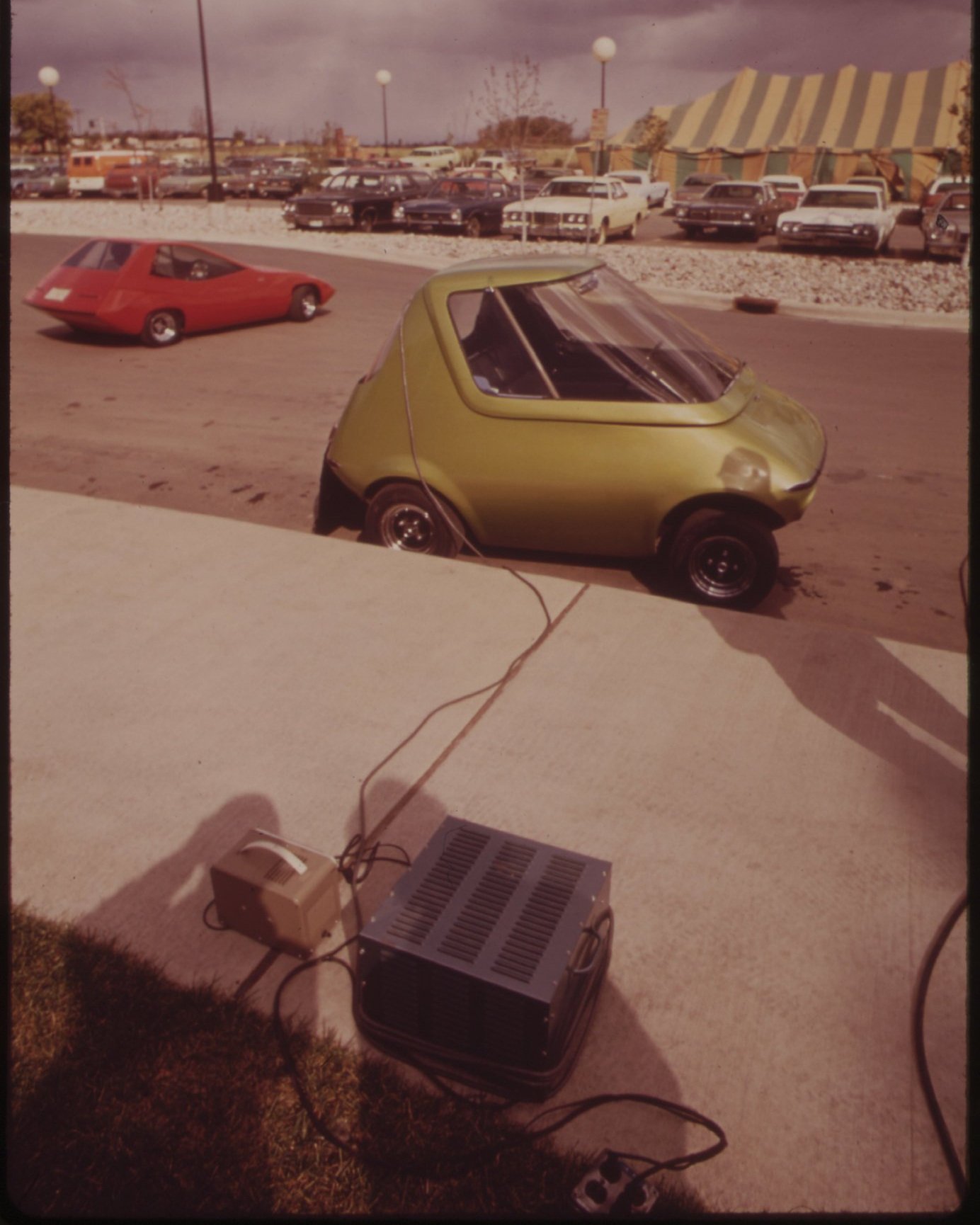

Image: Courtesy U.S. National Archives

Tainted supply chains drive interest in Corruption-Free battery maker

TRIBHUVAN INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT – KATHMANDU, NEPAL: There was a time when travelers sojourned to this Himalayan mountain paradise seeking enlightenment or to try their luck scaling the world’s highest peaks. But now, it seems, they travel here to cue up in a uniquely Nepali take on security checkpoints.

Security lines here don’t scan travelers for bombs or guns, but for smuggled gold.

“Corruption,” sighed a tourist guide, as he stood in a long line behind a dozen Buddhist monks having their holy crimson robes scanned for contraband mineral wealth.

These security checkpoints attempt to stem the flow of corruption that reaches the center of Nepali society. Last month, Dipesh Pun, son of the country’s previous vice president, Nanda Bahadur Pun, was arrested in connection to roughly 150 pounds of illegal gold seized at this exact airport screen in July of 2023. Pun’s arrest was part of a Nepali transnational investigation into sophisticated smelting, transport, and distribution of illegal mineral wealth, mostly between Chinese nationals and members of the Nepali government.

Given such levels of corruption, successful battery manufacturers need both a track record of managing a fraud-ridden world and trusted legal frameworks to serve automakers struggling with unstable supply chains. An excellent example of a corruption-resilient battery maker is an otherwise unglamorous Belgian materials science and recycling company called Umicore (UMI).

Nepal, it appears, has devolved into a kind of “gold smuggling hub” for the entire Eurasian continent. This illegal wealth is warping an already fragile Nepali economy. Since 1990, the United Nations’ Human Development Index has consistently ranked Nepal well below the global average for lifespan, access to knowledge, and standard of living. But during those same decades, the country has witnessed a real estate boom that rivals any place around the world, including New York, Tokyo, and Delhi.

Officials publicly say that these record property values were driven by Nepal’s remittance-based economy. Nepali labor, mostly young men, travel to India and the Middle East for multi-year work tours, where excess wages are sent home. These foreign currencies are then leveraged by easy bank loans tied to the rising values of low-cost family farm land, being broken down and revalued as housing stock.

But in private, many Nepalis say that just as important to the spike in real estate is illegal gold and silver from foreign investors, who speculate on real estate. “The secret for the average Nepali to get ahead is to buy or sell a home with foreign gold, then turn around and rent a flat in that home to other foreigners who pay in hard currency,” explained one wife of a government official.

Nepal’s systemic corruption very much fits into a larger pattern of fraud around the globe. Corruption tracking and advocacy group, Transparency International, ranks Nepal as the 108th most corrupt country out of 180 tracked nations. But India, which has an economy roughly 200 times as big as Nepal’s, scores 93rd out of 180 countries. China scores 76th. Such corruption is not limited to Asian nations. Bottom-of-the-ethical barrel Venezuela scored second to last in Transparency International’s survey. Some 87% of Venezuelans felt corruption was a major problem, and a full 50% admitted to paying a bribe in the past 12 months.

Demand for goods and services in today’s global economy may ebb and flow. But the world’s hunger for graft seems to know no end.

The Gross Corruption Product

Cost estimates for corruption on a global scale are rare. And not for lack of trying. An 1850 French research paper, called Histoire Financière De La Situation Financière et Du Budget De 1851, bemoaned that as much as anything, the lack of accurate corruption estimated made planning and budgeting difficult. Machine-aided searches of 130,000 cited reference works on international graft, yielded few concrete models on the cost of large-scale fraud.

That’s surprising because back-of-the-envelope estimates for a “gross corruption product” are reasonably easy to flesh out.

Transparency International estimated that 28 out of every 100 Chinese paid a bribe over the past 12 months. That’s middle-of-the-pack palm greasing by global standards. Denmark, the world’s most honest country, reported just 1% of its population paid a bribe. But China has 1.4 billion Chinese, implying that something like 400 million off-the-books fraudulent transactions took place in the past 12 months. The total fraud involved is not knowable, since the Communist Party of China does not file tax returns. But with nearly 30% of the population cheating, it’s safe to assume that a decent chunk of China’s reported 2% growth in GDP is being skimmed off the top.

Chairman Xi is both more corrupt – and poorer – than he cares to admit.

Corrupted Batteries

Corruption’s effect on specific markets is also surprisingly easy to rough out. Take, for example, the minerals needed for batteries for electric vehicles. Since the West began to decouple the sourcing of cobalt, lithium, manganese. and other rare earth metals from China, there has been a steady drumbeat of sourcing such minerals from Africa. In 2022, 12 global automotive associations signed commitments to develop the African automotive industry. Various African nations have struck deals to export minerals needed for electric vehicles. And Western car makers Chrysler, General Motors, and others made major investments in South Africa as the preferred source for the minerals needed for EVs.

Opinion is building that South Africa will emerge as a reasonable alternative to China for minerals needed for batteries. But that growing support seems to ignore the country’s high levels of violence and corruption. South Africa has the grim distinction of leading the African subcontinent in police deaths of civilians per capita. Police deaths of civilians per capita accurately compares the violence of one society to another. South African police kill about twice as many civilians as the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is sobering considering the Congolese have struggled through a series of low level civil wars since it ended its colonial period in the late 1960s.

Transparency International has put South Africa on its watchlist for especially corrupt economies. It reported that even though South Africa’s apartheid regime ended more than 30 years ago, corruption levels in the country have risen steadily over the past half-decade.

The direct reports of business fraud are staggering. The former head of Eskom, the country’s largest power company, André de Ruyter, wrote a memoir of the deep theft he faced during his 3 years managing the company. De Ruyter struggled with bogus fuel deliveries, overpriced safety gear, missing equipment, and death threats. As a result, the power utility struggles to meet the power demand of the country.

Estimates suggest it will take South Africa at least 5 years to overcome such shortages.

The Corruption-Resilient Battery

Umicore is not Tesla. The company got its start all the way back in 1906, as the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga or UMHK. UMHK was the Belgium-English joint venture specifically set up to rip as much copper, uranium, and other minerals from 7,700 square miles of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. The profits were obscene, as were the abuses. It all lasted until 1966, when the Congolese finally threw the Belgians out and nationalized the mines.

Umicore got its start as UMHK during the 20th-century twilight of the Colonial Era. It operated mines in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. | Photo: Creative Commons via Wikipedia

It was Nelson Mandela who pointed out that freedom liberates both the oppressed and the oppressor. Once out of the Congo, UMHK could then focus on adding value, instead of destroying it. The company slowly built or bought various refining, processing, and material sciences businesses. In 1989, the entire operation was rebranded as Umicore. In 2022, the operation saw a peak sales of $27 billion across various emissions control, precious metals processing and battery-making operations in several European locations.

Today’s Umicore, however, frightens most investors. And for good reason. Revenues cratered last year by about 26%. The company's non-battery operations faced major pressure, as China’s economy slowed. Sellers of its stock have outstripped buyers for more than a year. And there is probably more downside in this equity, as the global economy continues to cool.

Refining is a tough game these days.

But Umicore has adapted to worse. And sure enough, behind the falling sales, the company made the operational adjustments that increased balance sheet equity by about 10% and cash flows from operations jumped by about 50%. Umicore just landed $316 million in low-cost Eurozone financing to scale its battery business. It is investing in flexible battery-making technologies that can adapt to shortages of materials and evolving battery chemistries.

Better yet, Umicore is fabulously cheap. America’s European heritage is not trendy now, so its companies tend to get overlooked. Umicore’s current price-to-earnings ratio is $12.20 per share, or lower than its lowest levels back in 2015. As a contrast, in 2022 investors bid up the price-to-earnings to $89.20. That is real value.

But what cements Umicore as a corruption-resilient pick for the batteries needed in electric vehicle is spending time in a corrupt economy like Nepal’s. Getting things done in this mysterious, beautiful country is a challenge. This place can be slow, dirty, poorly managed, and flatly exploitative of its own people.

It takes a tough-minded business like Umicore to operate in corrupt economies like Nepal and South Africa. As unglamorous as this operation might be, it’s got the grit to offer the most valuable asset of all: Peace of mind in a world struggling to come to terms with just how corrupt it has become.