Manufacturing a Recovery: RPM International (RPM)

Could A Surge in travel and an Unglamorous Manufacturing Spurt Signal the worst of the Recession is behind us?

THE OLD BELL INN: DELPH, ENGLAND – Working one’s way through the over 1,500 choices of gin available at this gloriously quirky traditional English pub, is a surprisingly effective path to a jolt of a new idea:

Could the economic worst be over?

The fall in real wages has been tough on consumers. Consumer credit debt is touching all time highs. But quietly, these low real wages have been a boon for businesses. The companies that have adapted are probably paying less for labor in inflation-adjusted terms, meaning value is quietly piling up in pools overlooked by one-size fits all regulators.

One place where today’s successful businesses are harnessing value is productivity. In August 2023, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its Total Factor Productivity data. Productivity here is defined as “output per unit of combined units” or what can be made from a given amount of work and goods. We took this BLS data and normalized it per 1,000 workers and found that of 88 tracked sectors only 7 showed negative productivity.

And some sectors, like material coatings for industrial goods, saw dramatic increases.

Privately held businesses such as Endura Coatings, a Sterling Heights, Michigan, automotive coatings operation and Houston-based MetCoat, which serve the oil and gas sectors, stand out. As for publicly traded companies, PPG is the massive coatings conglomerate that capture all stages of industrial finishes. Though the giant has been beaten down due to global supply chain concerns.

We would start with a look at RPM International (RPM), a $7.3 billion global coatings, sealants, and construction material company based in Medina, Ohio. RPM is exactly what you would expect a giant paint company to be: It features reasonable growth, good dividends, and products that sell everywhere. Buyers of the stock have outstripped sellers for about a year. RPM is the perfect, reasonably priced lunch-pail operation that is ideal for a world distracted by hard times.

The Industrial…Evolution

Back in Delph, England, cozy sheep and dirt roads decorate the nearby English Midlands. But the crumbling textile and steel mills just up the road were ground zero for the Victorian-era Industrial Revolution. Both the American Confederate South and European-style Marxism were shaped by nearby Manchester. These lowlands, between the Forest of Bowland to the north and the Peaks District to the south, were the world’s first Silicon Valley.

As one compares the whiskey-like Genever gins imported from Holland, to the smoother Plymouth gins made ever sweeter by tonic trucked in from Scotland, it seems ever more likely that reports of a recession may be damned: A jittery, centrally managed post-pandemic economy may have simply failed to notice that many of its woes are behind it.

Certainly spending time in towns like Delph, as lovely as they are, do nothing to soften the larger drumbeat of grim news. Markets are digesting yet another extended ground war, this time in the Middle East. What could be more frightening than realizing that Richard Nixon was the last American president before Joe Biden to openly support Israel during a full-scale war? Aptly dark jokes, now ask which central banker depresses markets more: Fed Chairman Jerome Powell or or the People’s Bank of China, Pan Gongsheng. The public sector is also ghoulish. England’s second largest city, Birmingham, simply closed down in the face of $1.4 billion in unpayable municipal debts. Only Detroit was a bigger urban washout.

No wonder gin sales are at an all-time high. There’s much work for liquid courage to do.

But step outside into the rainy weather and gusty winds – both in the industrial English heartland and over in Europe’s northeastern Italian manufacturing hubs around Milan – and an entirely different, more upbeat economic story emerges.

These times, while far from ideal, do have pockets of opportunity. Pretending otherwise misses all sorts of value.

Ignored Upside

Optimists these days start their argument with the bellwether for any economic ground truth: Air travel. Here are some touch points we noted in New York, Manchester, and Milan: intense crowds, overwhelmed air-service personnel, and deep demand. The IATA, a global air travel trade group, confirms that, though not back to pre-pandemic levels, demand for aircraft seats grew dramatically in 2023.

Overall economic activity also seems robust in Europe. Certainly rising prices and shaky demand worry business owners. But successful firms focused on niches, innovated, and worked through supply shortages. A local textile mill, for example, avoided supply shortages by provisioning its fiber from locally raised sheep. These low-cost, high-quality inputs were then woven up into world-class fabrics that captured high margins.

“Our woolens usually find their way to Saville Row suits,” said one mill owner, who’s planning to add a second shift to meet demand. (When asked if a lower cost option than a $6,500 London sportcoat could be found in America so a mere reporter could sample his wares, the answer was a polite, “Probably not.” )

The UK’s Office for National Statistics confirmed that the output for such consumer durables was up, though overall industrial sectors, which factor in battered industries like automotive, were down. That growth was part of a larger upbeat trend for European construction, road traffic, and improvements in real estate. Italy’s Istituto Nazionale di Statistica confirmed that the Italian construction sector grew by over 2% in August of 2023.

But probably the clearest data point on the robustness of Europe we found was the reservations now required on most days for a simple lunch at a low-cost, high-altitude mountain hostel such as the Refugio Campogrosso, in the foothills of the Italian Dolomites.

Demand is so robust, that not even a 7-mile, 2,000-foot vertical hike is enough to make for an open table. For one who has traveled overseas since the 1960s, this is just not a Europe that is sliding into a deep decline.

Miscounting the Beans

The disconnect between real economic growth and reports of business doom are hard to explain. But one never goes wrong in assuming tracking an economy's hard times is like tracking a person’s mood swings. Not everyone’s dark moods are the same. Neither are a society’s. In the U.S. the complex process of Business Cycle Dating is managed by an important committee at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Unless one is up to speed on the concepts of the “densities” of economic expansion, contraction, and “mixture,” one is probably not using the logic of recession with enough rigor.

The already complicated process of measuring downturns has been worsened by a once-a-generation wave of inflation. Scholarship indicates that rising prices hide how value is measured, how real estate is priced, how securities perform, and how output grows. When it comes to quantifying a 2% economic contraction, price increases of even 5% or 8%, can cause a major distortion.

Inflation’s effect on discerning recessions has been made even more complicated by unprecedented centralization of narratives among financial regulators. For the first time we can recall, bellwether central bankers like Jerome Powell, Christine Lagarde, and Andrew Bailey essentially announce the exact same rate increases, at the exact same moments, to render the same economic projections for a vast global economy.

How these supposedly independent central banks are synchronizing their messages is not known. But they are not the only central bankers acting as if the vast global economy were a single market. The Swiss-based Bank for International Settlements, which was the global financial organization that collected German War reparations following the First World War, regularly publishes transcripts of central banker speeches and comments. For reasons no one can explain, supposedly unrelated officials like Joachim Nagel, president of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Ales Michle, Governor of the Czech National Bank, and Jessica Chew Cheng Lian, Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Malaysia, all agree on similar market conditions, growth, and the cost of capital, no matter the actual state of their economies.

Until markets understand how the Czechs know what the Malaysians are doing, much less how the United States knows what the United Kingdom is doing, it is fair to ask how regulators can plausibly argue that the cost of capital in Miami is the same in Malaysia; or that the discount rate for that capital in Shanghai is equal that in Soweto.

Inefficiencies must be looming. It is time to explore the notion of “central bank arbitrage.”

Tracing the Upside

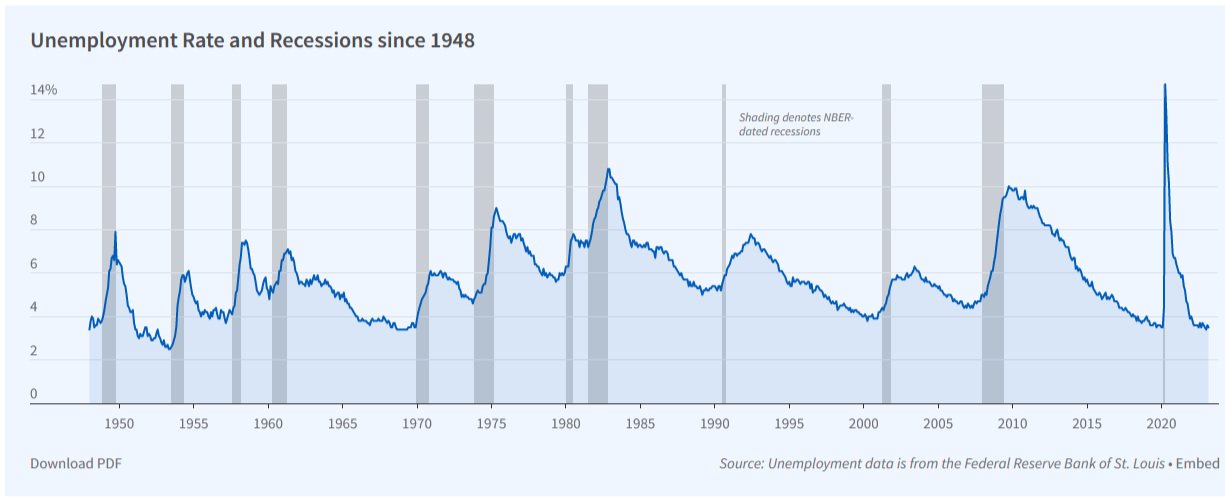

As of now, optimists make a good argument: Pandemic lockdowns drove unemployment to a perilous 14%. But stimulus dollars flowed to consumers to avoid a crippling recession. In those months after lockdown, smart business owners and market actors adapted their businesses and drove unemployment back down to rates at or below non-recessionary periods, at least according the National Bureau of Economic Research data pictured below.

But even though business drove unemployment lower, real wages fell even faster. Inflation quickly ate up whatever gains employees could capture. The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development estimated real wages fell by about 4%, at least in the top two-dozen economies in 2022.

Public funding drove a wave of inflation that eat into the real wage gains for consumers Meaning many firms now pay less for labor in real terms.

The fall in real wages has been tough on consumers. Consumer credit debt is touching all time highs. But these low real wages have been a boon for businesses. The companies that have adapted are probably paying less for labor in inflation-adjusted terms, meaning value is quietly piling up in pools overlooked by one-size-fits-all regulators.

Of 89 tracked categories, only 9 saw loses in productivity last year. Some sectors, like coatings and turbines, have seen dramatic gains.

Data indicates these gains were not flash-in-the-pan, post-pandemic improvements. They are part of long term growth. The Bureau of Labor Statistics also released its 10-year employment projections. The data clearly predicts roughly 5 million new jobs to be created over the next decade, with reasonable wage growth and improvements in core consumer demand throughout that term.

Productivity of this scale is simply not an economy flirting with disaster.

Getting On with Prosperity

Courage is still required to get comfortable with the idea that the worst is past us. As any economist will confirm, the relationship between productivity and actual economic growth is not fully knowable. What makes communists like Karl Marx, free-market lovers like Adam Smith, and middle-of-the-road European socialist Thomas Piketty who they are is how they view the flow of productivity into actual production.

The path to prosperity remains the same series of uncertain steps it always has been. But assuming that today’s productivity will lead to tomorrows prosperity in the future does simplify sniffing out value.

Improving productivity in sectors like coatings indicate turns operations like RPM International into attractive businesses.

Which of course, is the secret of sipping on gin, here at the bar at the marvelous The Old Bell Inn: Life may not be perfect. But for things worth tasting — with a bit of confidence — once past the bitter first sip, things improve.