Voodoo Mine Control: Nouveau Monde Graphite (NMG)

An astonishing 50 cm resolution satellite image by Planet Labs, exclusively for Brookside Research.

A Graphite Mining Company Unearths A Surprisingly Rich Vein of Mineral ASsets

KEYSTONE, COLORADO – Coloradans like to segregate mining, off and out of the way. It’s a good hour drive south to Leadville, where the National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum houses an aggregate of cavern tours and model earthworks. Vintage images from the 1880s of young mining men and women, most of whom never lived past 30, hang ever vigilant on the wall.

Most who live here struggle to grasp that their landscape of adventure parks, condos, and Denver’s largest reservoir exists side-by-side with newly invaluable mineral assets that lay hidden in the ground.

These days, the effective harvesting of newly critical minerals requires trusted governments, reliable economies, and known rules of law, or basically North America. Which leads us to an early-stage Canadian mining company called Nouveau Monde Graphite (NMG).

“There are no local mining experts left,” says one former geologist who now trains with ex-Olympians on Nordic ski trails cut at 9,200 feet. “There’s the big molybdenum mine over in Climax, a half-hour away. But that’s about it. This is just a mountain town.”

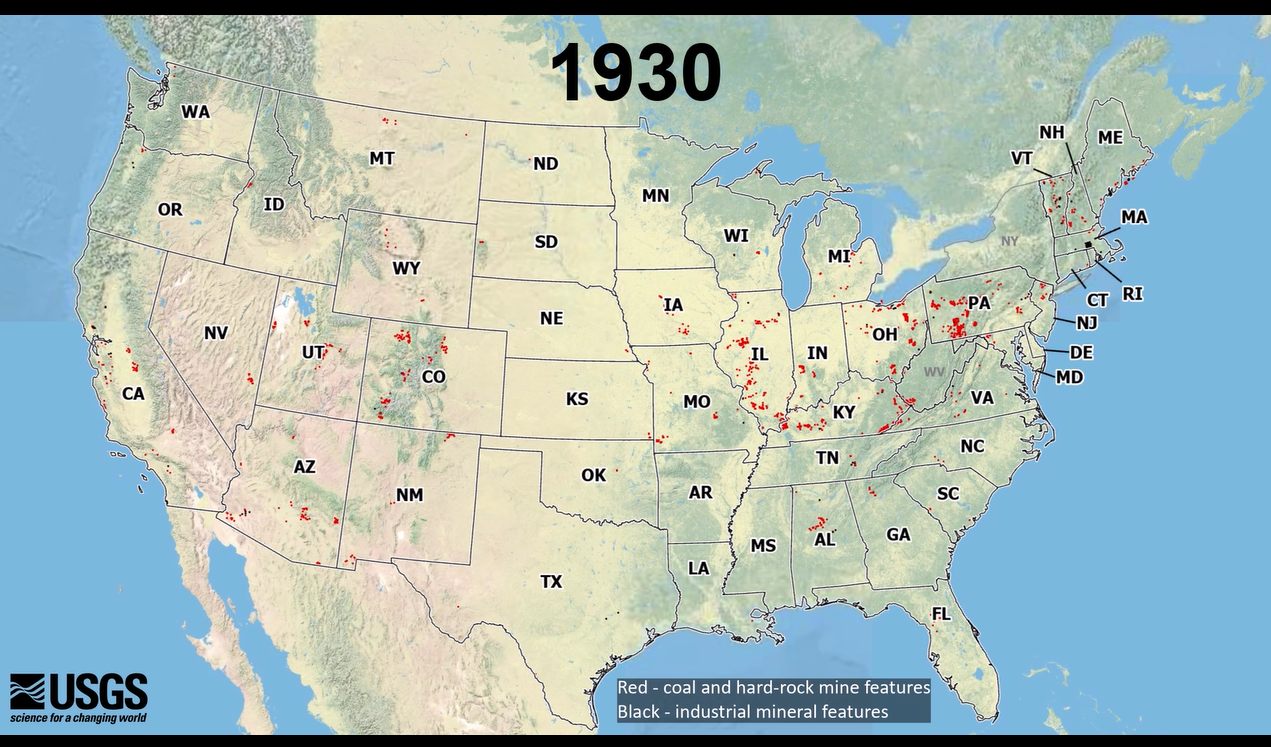

But are towns like Keystone really nothing more than mountain bedroom communities? That depends on who you ask. The United States Geological Survey Mineral Deposit Spatial Data confirms that only a few currently workable claims still exist in Colorado. The Red Mountain mine, 45 minutes to the northeast, is the rare example.

Survey data indicates only a few workable mines left in choice resort communities like Keystone, Colorado.

But widen that search to include the swath of existing mining assets and the potentially recoverable geological resources that include newly critical minerals needed for the batteries that propel the next generation of electric vehicles?

The wider mining landscape overwhelms the ski areas and shopping malls.

Factor in all available mining assets and critical materials needed for electric vehicles, and the ski resorts and condos become afterthoughts.

What is continually unsettling is how easy it is to explore the readily available mining resources near Keystone. The abandoned Erickson Mine is a beginner’s downhill ski from an alpine run called Strayhorse. The Rainbow Mine, one of dozens similarly named claims across the country, is just a few snowboard turns of a traverse the locals call Goalpost Gully. The tension between what minerals are known to be in the ground and what is actually there to be exploited has become a central theme to today’s mining industry.

“Commodities markets have lost their place as the top of the risk radar,” wrote Trevor Hart, head of mining for KPMG International in a 2022 report. Hart believes that, these days, a mine’s worth is as much about environmental concerns and regulations as it is about the price of the mineable asset.

The tension between what is currently mined and what could potentially be mined is not limited to Colorado. U.S. Geological Service data captures the growth of available American mineral deposits over the past century. Since 1888, recoverable geological assets have come to sprawl across the entire lower 48 states. Environmentally conscious states, like California, Colorado, and Wisconsin feature particularly lucrative resources.

Survey data indicates that more we look for mineable assets, the more we find.

Serious mineralogical resources exist throughout the lower 48. Note the concentration in states like California, Colorado, and Wisconson.

Mining experts go utterly mum when coaxed toward any sort of estimate of the total value of all the potential mineralogical resources in North America. However, the U.S. Geological Survey, which acts as the kind of Federal Reserve Bank for rocks, does offer trusted estimates that carve out the sheer scale of America’s geologic resources. The market for domestically mined, raw, non-energy materials touched $98.2 billion in 2022. That, in turn, fed a domestically processed mineral market of $815 billion. That fed off into a larger non-energy geological economy of roughly $3.6 trillion. The total U.S. domestic gross product for that year was $25.4 trillion.

Said in plain, non-miner English: 14 cents of every dollar every American spends, comes straight out of the ground. But how many of those same Americans know from where, or how, that mineral wealth is culled.

Working the Mine

No society – be it human or otherwise – remains unaltered by mining. Exhibit A is the happily mated pair of 18-inch-tall adult pangolins. These shy, scaly anteaters use their claws and scaly snouts to mine out underground insects by the millions. In the process, the mammalian equivalents of underground mechanical excavators engineer intricate vaulted burrows that are high enough for humans to stand in. Sadly, the pangolin’s mining prowess makes it among the most trafficked and endangered species on earth.

This 18-inch high pangolin mines insects by the millions, and in the process, builds caverns tall enough for humans to stand.

And while we humans like to divide history into the different tools we used to shape it, what we really do here on Earth is mine. No matter whether the age was of stone, bronze, iron, or silicon, humans tend to run out of the materials lying around on the surface. So the digging must begin.

The Neolithic flint mines, in Spiennes, Belgium, date from the 5th millennium B.C. They are among the eeriest – and frankly most lovely – ancient European structures still in existence. These UNESCO World Heritage sites feature a vast network of spacious underground galleries, load-bearing columns, and shafts that light, aerate, and provide surprisingly complex logistic support.

There was even art scribed on the walls, meant to brighten the burden of striking and quarrying 6-foot blocks of flint to surface workshops, that were then minted into the tools needed to farm, fight, and make for early civilized human life.

Over the 8,000 years since, mining has remained one of the toughest businesses around. The still surprisingly apt 1903 text The Economics of Mining warns that probably 95% of all commercial mining enterprises fail. The authors, which included former President Herbert Hoover, boil down the risks of mining into five direct commandments that deserve a prominent place in every mining investor’s imagination.

Please read the following carefully:

The Five Commandments of investing in mines, from the 1903 text The Economics of Mining, which former president Herbert Hoover helped write.

The collateral damage of mining is not limited to the bottom line.

One of the Center for Disease Control’s least controversial data sets its Mine Disasters, 1839 to 2021. No one disagrees that in the early part of the 20th century, miners died basically daily. The year 1910 was a particularly bad one: 25 total incidents caused 934 deaths in the U.S. In France, roughly 1,100 died in a single accident at Courrières, in northern France. Explosions were the usual culprits.

Mining has gotten safer, but remarkable risks remain. A 2011 Rutgers University study of Chinese mining accidents indicates that over seven years, more than 9,000 incidents occurred in coal mining alone, yielding something on the order of 23,000 fatalities.

The realities that make mining both unprofitable and dangerous weigh heavily. Valuing a mine is uncertain. Measured mineable reserves are a challenge. Exact capital costs are blurry. Engineers’ estimates are best guesses. Repairs can be serious. Shafts must be drilled. Cash must be flowed. Costs must be managed.

And each can vary dramatically by where and who is doing the counting. That assumes everything is on the level, which it very often isn’t. The 1968 The New Yorker essay on the Texas Sulfur insider trading case by John Brooks, called A Reasonable Amount of Time, chisels out just how easily mining can unearth nothing but deceit.

There’s a reason why this story is one of Bill Gates’s favorite business tales. Mining is a heavy lift.

Not-So-Rare Earths

Until the past decade, the mineable elements that went into middle-technology applications in cellular phones, flat screens, and aviation were geologic afterthoughts. For example, the 15 or so rare-earth elements that can flow electrons about in clever ways in magnets, light-weight structures, and, most importantly, batteries, generated little industrial demand, wrote Keith Long and others, in a 2010 U.S. Geological Survey report.

There’s a good reason for a miner’s indifference to rare-earth minerals. None are particularly rare. Some are more common than copper. And few rare-earths are particularly easy to mine. One California rare-earth mine we studied had, by our count, 35 fully different processing steps, including steaming, grinding and pounding. More heavy lifting indeed.

What’s involved in processing rare-earth minerals from as single kind of ore from a mine in California. That really is 35 or so steps.

Not surprisingly, these mid-tech mineable materials have until recently been off-shored to low-cost markets, with cheap labor that work on lots of land. In 1993 about 38 percent of global production of rare-earth minerals occurred on the Chinese mainland. By 2008, China accounted for probably 97 percent of the rare-earth mining. And when the sphere of similar easy-to-find, but still exploitable, mid-tech materials is widened to include lithium, nickel, and cobalt, U.S. production is vanishingly small.

In 2022, for example, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that the United States had no domestic graphite production whatsoever.

But such middle-tech mineral complacency has changed. Early in 2022, the United States Geological Survey expanded its List of Critical Minerals to include a full 50 non-fuel mineral materials that were deemed essential to economic or national security. Some 15 new materials were added over the previous list in 2018.

Overnight, what were once seen as easily available minerals, including cobalt, nickel, and graphite, become newly “critical materials” that must be sourced in a strictly redrawn global market. A market that explicitly muscles out China and Russia.

Many experts are calling for intense “critical material” shortages.

Graphite America

Practically appraising the emerging critical minerals market will be complicated. Clearly momentum is building around U.S. domestic capacity. In 2021, Alabama governor Kay Ivey announced an advanced graphite processing plant. And there is a growing complex of lightly capitalized graphite miners and processors within the North American sphere. U.S.-based Graphite One appears to have a viable claim in Alaska. Far larger GrafTech is another graphite processor, with roots in Ohio. Vancouver-based Leading Edge Materials has several claims in Sweden and Romania. Syrah Resources is another graphite player, with more of a focus on the Africa continent.

By our eye, graphite miners and processors are the highest concentration of $5 stocks we have ever seen.

But all these graphite players face the same challenge: Mother Earth places her mineral wealth where she pleases. She cares not a whit for the views and amenities of destination real estate like that in California, Mexico, or here in Colorado. The hidden tensions about what land gets to be used for what can flare. In 2022, $500 million in U.S. tax dollars were spent to transform mines into Clean Energy Hubs, whatever that means. That was after a 2021 pushback from the Nevada-based Shoshone-Paiute tribe that worked hard to halt a new lithium mine being carved into their land.

A Canadian mining company called Nouveau Monde Graphite, located in Eastern Quebec, north of Montreal, seems to have the touch for graphite.

Which brings us back to Nouveau Monde Graphite (NMG).

To us, this Saint-Michel-Des-Saints, Quebec-based operator offers the right mix of matching the ancient realities of mining, with the modern specifics of getting and processing the newly valuable graphite out of the ground.

Graphite From Space

Mining graphite is not tricky. The carbon-ish material started finding applications about 100 years ago. And true to form, with other newly critical materials, graphite is not rare. It can be manufactured synthetically, using an electrically heated resistance furnace, from almost any organic material. An excess of burnable carbon is all that is needed to create different grades with potential applications in rocket nozzles, coatings, and critical components in batteries.

But what makes Nouveau Monde compelling, is that its graphite operation can be seen and validated. Comparison of available public satellite imagery of open pit mines 150 miles north of Montreal, near company headquarters, can be compared to proprietary satellite images we had taken in the past weeks. Simple side-by-side comparisons show the progress of a new mine over the past 18 months.

Graphite mines are reasonable assets to explore from orbit. To the right is publicly available imagery from roughly 18 months ago. To the left, is recent live image from earlier this month.

Monitoring real activity is 90% of the mining equation.

A higher-resolution image, tasked from a targeted sensor flying overhead, reveals deeper narratives. Smoke from the processing furnace can be seen. Roads are being plowed. So product is being process. But note how the plowing is limited to the production area. The mining areas, off to the left, remain untouched.

A 50 cm resolution image confirms smoke activity in the furnace, plowed roads in the main processing area. But note how the mining sections are not plowed, indicating enough supply for at least the winter.

That indicates Nouveau Monde has enough material stockpiled through the winter to meet demand.

Given this eyes-on validation, when Nouveau Monde announced this week that it sold $22 million of new common stock to raise money, it was fair to assume that that investment will go straight into a reasonable graphite market that promises returns.

Factor in the firm’s solid balance sheet, the fact that total assets grew last year, and that capital expenditure peaked in 2021, we can squint past the fact that the stock is trading a low of $4.25. And the operation is burning cash, like a graphite blast furnace, at the clip of $41 million last year alone.

Other imagery indicates that competitors are starting similar mines nearby. That all validates the area that we are watching this section of eastern Quebec, emerge as the Silicon Valley of graphite.

Once this wealth is unlocked, only time will tell how it impacts accessible assets everywhere, including here in Colorado.