Netflix (NFLX): New Media or Just Another Rerun?

Photo by Freestocks.org via Pexels

A look BackWARD Suggests the Streaming Juggernaut is Merely a mature media and distribution company

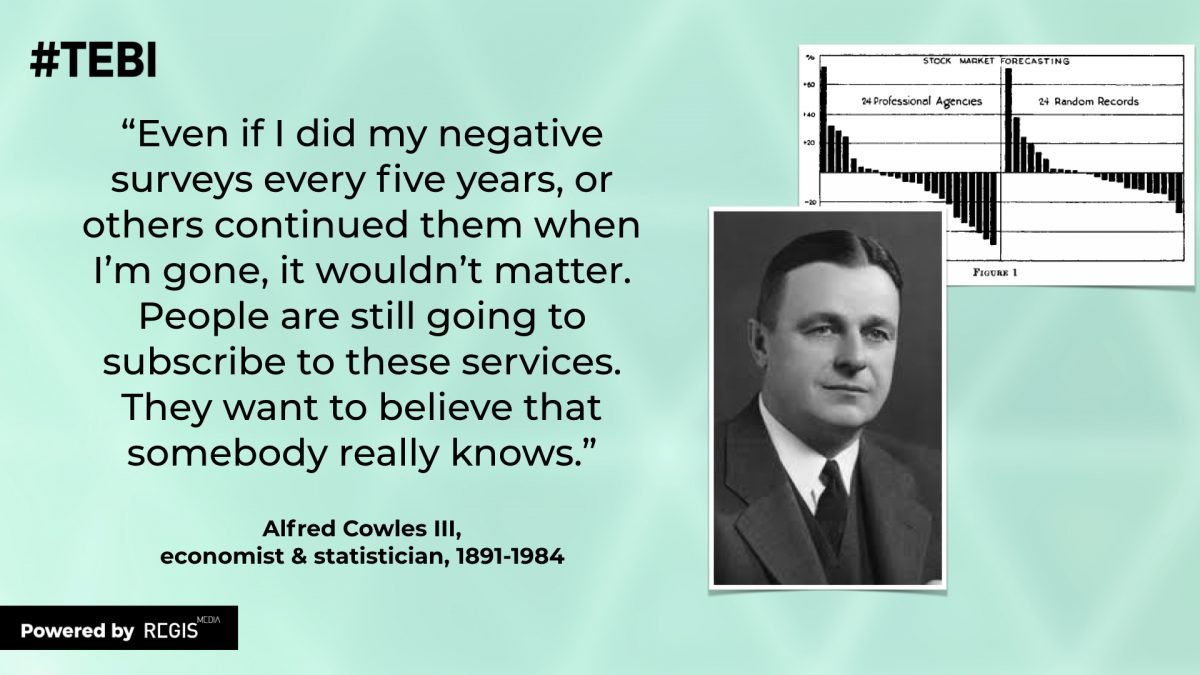

Isn’t it delicious when history repeats itself? Allow us to serve up this succulent media moment from 1932, when Alfred Cowles III read his then-groundbreaking paper to a special joint meeting of The Econometric Society and the American Statistical Association.

“The facts are rather clear that the great mass of investors, who based their actions more on instinct and a subconscious sense of the possibilities of the future, than they did upon elaborate statistics and analyses,” read Cowles from his text Can Stock Market Forecasters Forecast?.

Here again, history gives us the tools needed to value the once-high-flying Netflix (NFLX). Currently, the company’s stock is trading at around 16 times earnings at about $110 per share. At one point, it traded at more than 45 times earnings at $500 per share.

The 1929 stock market collapse set of a wave of innovative market analysis and industry soul-searching.

Cowles III was the grandson of Alfred Cowles, founder of The Chicago Tribune. And the son of Alfred Cowles II, who ran both that paper and the American Radiator Company. Cowles III was presenting to a fast-growing, newly formed community of economists and mathematicians, all struggling to come to terms with the single greatest financial catastrophe in history: The Stock Market Collapse of 1929.

Cowles had spent the five previous years digging through the forecasting efforts of 45 professional financial agencies. No mean feat, considering at that time, typesetting was done with hot lead and data was transmitted one bit at a time. By telegraph.

Cowles would not be denied. He studied 7,500 separate recommendations from over 75,000 entries for the stock picks from 16 financial services firms. He studied the investment return from 20 fire insurance companies. He also tracked the predictions of 25 financial publications that had speculated on the overall future course of the market over the previous half-decade.

And just to make his point, Cowles also tracked the 26-year forecasting record of William Peter Hamilton, the then-longtime editor of The Wall Street Journal.

Overall, Cowles was skeptical. “Some of the forecasters seem to have taken a page from the book of the Delphic Oracle, expressing their prophecies in terms susceptible of more than one construction,” he wrote.

In sum, Cowles found that the best returns he saw were in the 20% range. The laggards felt losses in the 33% range. More firms lost than gained. And Hamilton? His mean annual return over 26 years, was 5.7%. That’s roughly the yield from dividend income for stocks for that period.

Cowles was one of the first to quantify that, save a select few, market performance is hard to distinguish from pure chance. (Image courtesy: EvidenceInvestor.com)

Cowles was one of the first to sense what most modern markets now take for granted: Except for an elite small circle, given enough time and enough players, return is hard to distinguish from mere chance.

The Proper Range of Value

What Cowles was trying to quantify was the flow of more conservative valuation models that stemmed from stunned economists and statisticians struggling to learn from the collapse in 1929. A 1930 paper from Malcolm C. Rorty , a manager at AT&T and cofounder of the National Bureau of Economic Research, summed up the invictive.

“We were warned that we must not sell the United States short. We were told that we must consider only earnings and must pay no attention to physical values,” said Rorty. “We were looked upon as hopeless pessimists and conservatives when we suggested that some of the old economic laws still held force, that business depressions still were possible.”

Rorty’s analysis led him to believe that company valuations – no matter their class, sector, or technological prospects – fell within well-defined bands.

“In general, it will be found that the application of the preceding method leads to values of common shares which rarely, if ever, will exceed 20 times current earnings, and very generally will fall nearer the traditional ratio of 10 times earnings,” he wrote.

Which brings us back to the new-media tearjerker known familiarly as Netflix. During the pandemic, all eyes were on the once-innovative streaming video service. But now that society is opening back up, subscriber attention is harder to keep. And many are letting their monthly Netflix access lapse. Netflix suddenly feels like a mature media company, operating in a risky, low-margin business of making and distributing a variety of movies and periodic video narratives.

Many of its current shows struggle to find an audience.

Meme culture is wondering aloud about the quality of Netflix shows.

Internet meme culture openly mocks the poor quality of its original programming. If Stranger Things 4 and reruns of All American are any indication, the Internet may be right. The 16 times earnings Netflix currently fetches is probably a bit rich.

The 13 times earnings that an established distribution and content company like Comcast features are probably closer to correct.

Suddenly, the way is clear to find a proper value for Netflix: The company could find the efficiencies needed to improve profits. Analysts say it has a whopping $23 billion in movies and shows in the production pipeline. Money could be saved. But those close to Hollywood are adamant that Netflix management is flatly resisting change.

That leaves valuation pressure to depress stock prices. At a Comcast-like 13 times earnings, $85 a share feels about right.

Until then, there’s not much more to do than catch up on the random off-shore crime drama that’s actually worth watching. The Danish procedural thriller Borgen: Power & Glory is not to be missed.