Oracle (ORCL): The Less-Is-More Tech Bet

Image Courtesy: Strange History.net

An Old-School Tech Behemoth Flaunts Cash Flow Over Internet 3.0 Hype

Oracles are worth listening to, from time to time. Particularly, when they reify as nominally beaten-down tech companies, such as the Oracle Corporation.

Oracle first emerged from the business software mists back in 1977. That’s when a then 30-something software product manager named Larry Ellison read an IBM research paper called A Relational Model for Large Shared Data Banks. The author, E.F. Codd, argued that any form of information could be explored by the relationship between data organized into a clearly named table with well-defined columns and uniquely labeled rows.

Ellison immediately grasped the commercial significance of Codd’s vision of a relational database: A company need not sell particular hardware like Apple Computer or software like IBM. Instead, Ellison saw the potential of building bespoke relational databases for paying customers. Ellison cobbled together a prototype and promptly landed a lucrative contract from the CIA. Overnight, clients grew to include the Department of Defense, many Fortune 500 firms, and foreign governments.

In the early 1980s, Ellison renamed the firm Oracle, after its most famous product. By 1986, the company went public. By 1987, Oracle was probably the largest database management firm on the planet.

1978 Photo of Oracle’s Founding Team. From left to right: Ed Oates, Bruce Scott, Bob Miner and Larry Ellison.

The operation quickly developed a flair for blundering around. A 1990 audit revealed Oracle overstated its earnings. The stock plummeted. Remember the Network Computer? That was Ellison’s ridiculous attempt to compete with the desktop PC. There were the dubious acquisitions of Thinking Machines in 1999, Siebel Systems in 2005 and PeopleSoft in 2006. But the 2010 purchase of Sun Microsystems brought in a true crown jewel: the Java programming language. But somehow Oracle used Java to sue Google. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. It still drags on.

By 2014, Ellison stepped down from day-to-day management. CEO Safra Catz, one of the few women to hold such a job, took over. And through it all, the financial world celebrated Oracle’s unique relationship to information. A 2018 report summed the firm's rare A1 credit rating:

The rating was due to “Oracle's strong business profile stemming from its leading market positions in some of the largest segments of the enterprise software market, large installed base of customers, high proportion of recurring revenues, and strong profitability.”

But Oracle’s lucrative relation to information was about to turn sour.

Oracle Runs on Unstructured Fumes

By the mid-2010s, businesses began to get comfortable with data that was more and more disorderly. Expanding digital storage, faster processors, and machine automation allowed companies to keep all sorts of unstructured text-heavy business information. Firms began to store vast archives of loosely organized pricing data, Web-marketing results, and even conceptual factual definitions.

Estimates say that in 2020 there were 32 zettabytes of unstructured business information. By 2025, that figure might reach 130 some-odd zettabytes. Inside these exploding galaxies of poorly-organized information, Oracle’s culture of managing tightly-engineered datasets began to be less effective.

The firm attempted to adapt. The nickname “Big Red” emerged as the operation tried to offer “everything enterprise.” Oracle sold a full suite of on-premise software, cloud-based systems, and software-as-a service. But the unstructured data market was not Oracle’s core competency. The operation began to get a dark reputation for deeply entrenching itself inside a customer’s IT infrastructure, only to gouge them for costly upgrades and repairs when software did not perform as expected.

Sloppiness became a business strategy.

That opened the door for low-cost competitors. EnterpriseDB’s open source PostgreSQL tool landed serious clients. Major investors, like Bain Capital bet against Oracle. Oracle’s cloud service offerings could not compete with Microsoft Azure or Amazon Web Services. Performance suffered.

In 2020, cash flow from operations retrenched to 2010 levels. And if capital spending was backed out, and free cash is considered, Oracle’s performance has still yet to recover.

Operating inefficiency has become a major issue.

Markets quickly realized that Big Red, for all its power, struggled to tell the Web-unicorn story of limitless growth. Over the past half decade, except during the peak of the covid fever dream in 2021, ORCL has underperformed against the major indexes, like the Dow Jones Industrials.

To the point where, even the simplest index outperformed company equity.

To make it all seemingly worse, Oracle went out and paid $28.3 billion – in cash no less – for a medical records company called Cerner. The deal required regulatory approval and a serious management shakeup. A half a dozen executives left. Eight more came on board. Staff layoffs and restructuring will be measured in the tens of thousands.

Market analysts were not amused. By some measures, dozens of research and investment firms walked back their estimates for Oracle. But it was the Moody’s bond rating downgrade to Baa2 that captured the dim view of Oracle.

“The downgrade reflects Oracle's elevated financial leverage, its aggressive use of debt to finance large shareholder returns, and lack of any long-term financial policy goals,” wrote Moody's analyst Raj Joshi.

Oracle suddenly was being compared to Compaq, Palm, and Research in Motion. Tech giants stumbling around to find their footing on a new hostile world.

The Little Data Side of Big Data.

But here’s the strange enterprise technology thing. As bad as the news is for Oracle, it was actually less worse than its big-tech peers. The post-Covid era, at least for now, has rewritten the valuation narrative for large technology.

Oracle has been utterly spared the crushing devaluations of pure-play Web stories like Netflix and Carvana. And that’s not because these two firms were having problems creating hit shows, or selling cars that run.

Oracle’s performance absolutely dominated technology as a sector. Over the past 2 years, ORCL’s value basically doubled as a percentage of the value of the tech heavy Nasdaq 100 index.

Regardless, Oracle still outperformed tech-heavy indexes like the Nasdaq 100.

The rationale is easy to see: Here’s a tech company with a track record for rich return, that also features old-school cash flow and about a 2% dividend! Not bad at all, in this day and age.

But on a deeper level, markets are sensing that Oracle is now operating in an information science market it was created to succeed in. Customers are coming to terms with the reality that more data is not necessarily better. The fast growing practice of data management – which is essentially deleting unprofitable information – has become a major component of the enterprise software market.

And in this less-data-might-just-be-more world, Oracle competes effectively. It has the clout to enforce its stricter vision of information with customers. Microsoft announced a cooperative arrangement with Oracle. Oracle was part of a market that drove unstructured data powerhouse Cloudera from the public market in 2021. Oracle has been announcing some intriguing deals. Oracle became the server backbone for Zoom during the peak of remote usage. It hosted the videos for TikTok as it migrated from overseas servers. It is managing the integration of toll collection for transport-startup Wipro. Oracle is also the de facto outsourcing choice for the lucrative consulting industry, including big names such as KPMG, PWC, Infosys, IBM, Deloitte, and Accenture.

Oracle even was the technology behind the study of humor in selling fashion.

Oracle can be a challenge for some to understand.

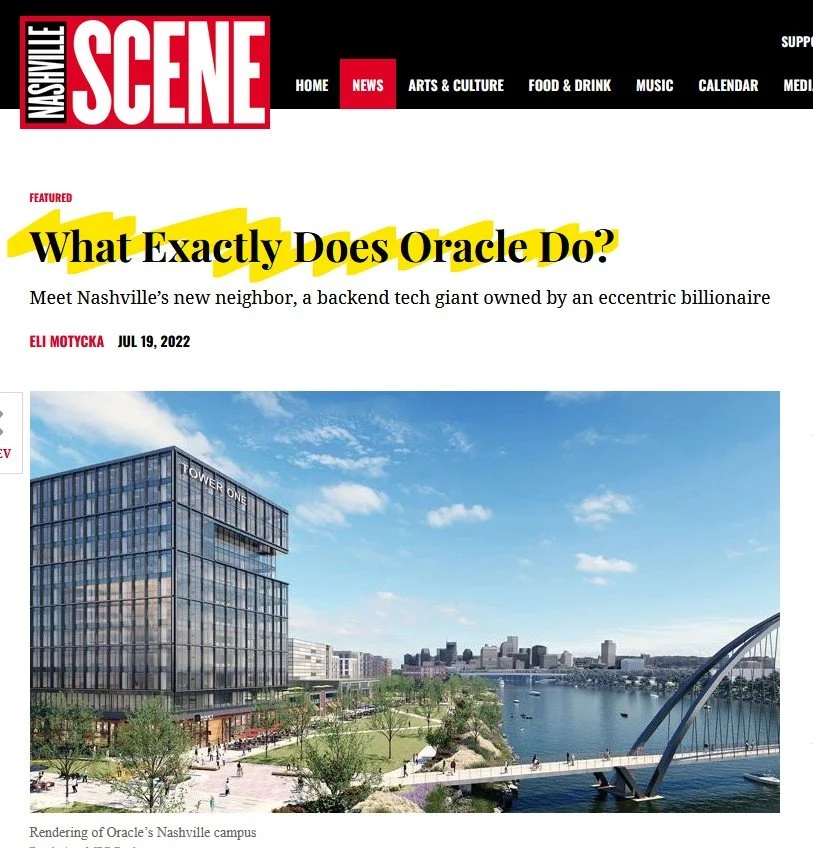

When the operation announced a new $253 million facility in Nashville, Tenn., the local media service, The Nashville Scene, ran a major story called “What Exactly Does Oracle Do?”

The short answer is, create value that not everyone sees.